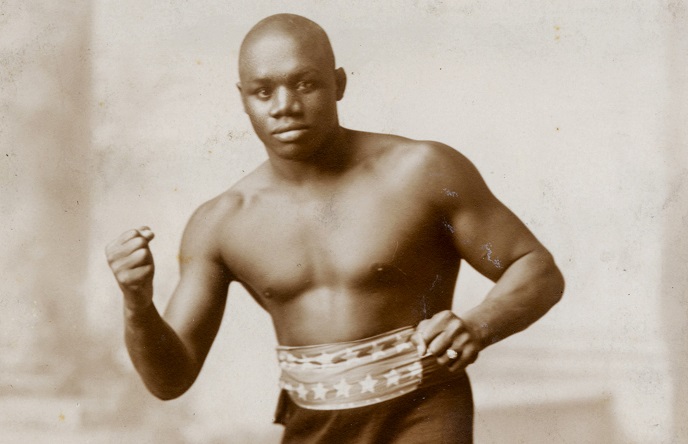

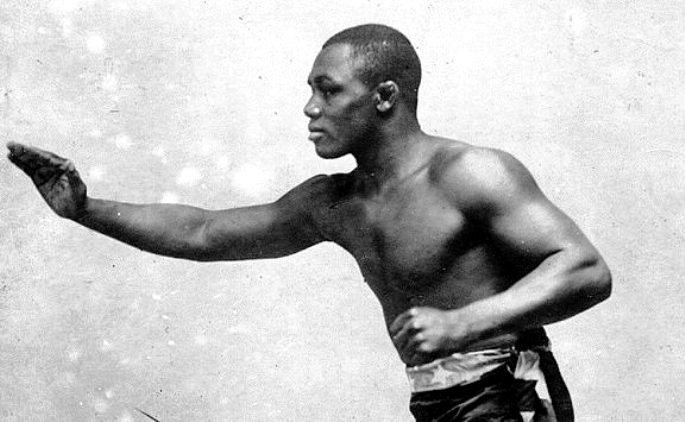

SAM LANGFORD: BOXING’S GREATEST UNCROWNED CHAMPION

Ninety-eight years and one month ago, arguably the greatest fighter never to win a world title entered the ring for the final time. Record-keeping being what it was a century back, there is no certainty how many times he had done so before, but it seems likely that his final bout was at least his 293rd. He had won at least 167 of the previous 292, but like most professional pugilists, his final outing would end in defeat. In his case, a loss was far from surprising: he was probably more than 40 years old at the time (his birthdate, like his boxing record, is not certain, but he claimed to have been born on March 4, 1886) and he was blind in one eye. Remarkably, he had been fighting with just one good eye for nine years – approximately one-third of a career that saw him compete from lightweight to heavyweight and strike fear in opponents and potential opponents throughout his different weight divisions.

His name was Sam Langford, and at least one of his opponents, Joe Jeannette, considered him the greatest fighter who ever lived. Langford squared off against Jeannette 14 times; one man who didn’t face him even once was the great Jack Dempsey, who once stated that, “The hell I feared no man. There was one man smaller than I, I wouldn’t fight him because I knew he would flatten me. I was afraid of Sam Langford.”

Langford stood just 5-foot-7, but he had broad shoulders and freakishly long arms, which allowed him to generate almost superhuman strength in his punches.

Another of his opponents, Harry Wills – like Langford, a posthumous inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and a man regarded as one of the greatest heavyweights of all time – declared that “when he knocked me out in New Orleans in 1916, I thought I had been killed.”

Wills said he had “met some hard punchers in my time, and all I can say is the hardest blows any of them ever landed on me were like a slap in the face from a woman compared to those bone crushing wallops of Langford. They seemed to go right through you.”

Wills recalled Langford’s body punches were so debilitating that when one landed, “you’d kind of look around half expecting to see his glove sticking out of your back. When he hit you on the chin, well, when that happened you didn’t think at all, until they brought you back to life again.”

“Fireman” Jim Flynn, who fought both Langford and Dempsey (and controversially knocked out the latter in the first round in 1917) proclaimed that Langford “could stretch a guy colder than any of them. When Langford hit me, it felt like someone slugged me with a baseball bat. But strangely enough, it didn’t hurt. It was like taking ether, you just went to sleep.”

“Gunboat” Smith, who also fought both men, declared that “nobody ever came close to being as good as he was during his peak. Why, old Sam could do everything. He could punch from any position and hit hard, too. He was a master boxer, difficult to hit. He would take all the heart out of you and then give you a fine pasting. He ruined me.”

Langford won titles around the world. He was variously the heavyweight champion of England, Mexico, France, Canada, and Australia. But he was never granted an opportunity to contest the ultimate prize, the heavyweight championship of the world, partly because he was too good and largely because he was black.

At the time that Langford was at his peak, notes Clay Moyle, author of Sam Langford: Boxing’s Greatest Uncrowned Champion, most states had prohibitions against fights between men of different races, and American newspapers “were filled with racist drawings of black fighters, grossly exaggerating features and printing derogatory descriptions of them such as “gorilla-like.””

This was the world in which Langford fought. It was why he had to fight Jeannette 14 times, Sam McVey 15 times, and Wills 17 times: because the opportunity to claim the greatest sporting prize on Earth was denied them. When Jack Johnson broke the color barrier and became the first black heavyweight world champion, it only served to stymie Langford’s dreams even more: such was the degree of fury and embarrassment on the part of white society at Johnson’s rule that, when he ultimately lost to Jess Willard in 1915, no black man would get an opportunity to repeat his achievement until Joe Louis 22 years later. And while Johnson was champion, he refused to give Langford a shot. He had faced Langford once already and had no intention of doing so again.

“Nobody will pay to see two black men fight for the title,” he initially said by way of explanation. And while that was almost certainly correct, he also let slip a more revealing admission: “I don’t want to fight that little smoke. He’s got a chance to win against anyone in the world. I’m the first black champion and I’m going to be the last.”

***

Langford was born in Weymouth Falls, Nova Scotia, the fifth of six children of Charlotte and Robert. His mother died when he was 12 and that same year he ran away from home, tired of repeated beatings from his father, ultimately finding work on a New Hampshire farm. He lost that job when he was caught fighting with the other boys who worked there, and walked to Cambridge, Massachusetts and thence Boston, the city with which he would ultimately be most closely identified and from which sprang his most popular nicknames: “The Boston Bone Crusher” and the less savory “Boston Tar Baby.”

While in Boston, he met a man called Joe Woodman, who ran a drugstore and operated a boxing gym. Langford worked at the gym as a janitor and also slept there. He began boxing amateur bouts before turning pro in April 1902 with Woodman as his manager. In December 1903, just 17 years old and with a mere 18 months of experience as a professional prizefighter (during which time he fought 24 times; boxers were a different breed back then) he took on and beat world lightweight champion Joe Gans.

Gans, to be fair, was not in the best of shape: he had fought just the night before and then caught an overnight train from Philadelphia to Boston. But still, it bears repeating: Langford was 17 and in his second year as a pro boxer; Gans’ record at the time was 136-8-17.

Nine months later, Langford had grown into a welterweight and fought a draw with champion Joe Walcott. Many ringside observers, however, felt that Langford deserved the victory.

Two years later, he faced Johnson, who was not yet heavyweight champ. Johnson dropped Langford in the sixth and boxed his way to a comfortable 15 round decision. But Langford was still learning his trade and working his way up to heavyweight; at the weigh-in, he tipped the scales at just 156 pounds, compared to 185 pounds for Johnson. According to Moyle, Langford would not reach his prime until around 1907; between then and 1912, he fought 53 times and lost only twice (a defeat to Jim Flynn he avenged two months later, and a disputed decision to Sam McVey in 1911). By that time, Johnson was champion; but he had seen enough to know he wanted no further part of him.

“The masses, white America, wanted a white champion, and they were looking for a white contender to defeat him,” acknowledges Moyle. “So, yeah, there was definitely not as much interest or as much money for a fight between two black men.”

Even so, Moyle argues that avoiding Langford was a “stain” on Johnson’s legacy.

“I know it was the smart business move, because he could make just as much or more fighting other men rather than risk his title against Langford. But Sam, clearly, for three or four years, was the leading contender for the title, and just didn’t get a chance.”

***

Like Johnson, Langford had a penchant for alcohol and women, and he also loved a postfight cigar. Unlike Johnson, however, he appeared to charm just about everyone with whom he came in contact.

“He was just a really happy, lucky, positive, and kind man,” says Moyle.

In some ways, Langford was an early Muhammad Ali, possessed of a quick wit and a predilection for calling his knockouts.

“Sportswriters loved him because he was so witty and quotable,” says Moyle. “In today’s world, he would be incredibly popular.”

By way of example, Moyle cites Langford’s February 1910 meeting with Wyoming’s reigning light-heavyweight champion Nat Dewey in Cheyenne.

“The weather was extremely cold and when Sam learned the last train heading for Los Angles coming through that night was scheduled to depart only 45 minutes after their fight was to start, he told his manager there was no way they were going to miss that train,” Moyle notes. “He broke the news to the fight’s promoter who begged him to carry Dewey for a few rounds to give the folks a show. But Sam declined, saying it was just too cold. When he entered the ring that night, he apologized to the crowd for what he said would be a short fight as he had a train to catch, and subsequently K.O.’d Dewey in the first round.”

***

In June 1917, Langford quit during a fight against Fred Fulton, failing to come out for the seventh round because of injury. The Boston Globe reported that “when Sam quit, his eye was closed tightly.” It was likely during this fight that Langford suffered the damage that rendered him blind in his left eye.

Despite his ailment, he fought on, continuing to win more than he lost, using his ring IQ to compensate for his loss of vision, sensing and feeling his opponents’ position and movements.

In 1923, aged 37, half-blind and far past his peak, he took a fight in Mexico City against Jack “Kid” Savage for the Mexican heavyweight title.

“I went down to Mexico with this here left eye completely gone and the right eye just seeing shadows,” he later recalled. “It was a cataract. They matched me up with Kid Savage for the title. I was bluffing through that I could see but I gave myself away. They bet awful heavy on the kid when the word got round. I just felt my way around and then, wham, I got home. He forgot to duck and I was the heavyweight champion of Mexico.”

The fight lasted just one minute and 45 seconds.

Eventually, Langford could no longer disguise his disability. Opponents would regularly target his semi-good right eye. Finally, in 1926, he was denied a boxing license and was forced to retire.

And then, remarkably, he all but disappeared from view, until Al Laney of the New York Herald Tribune tracked him down in poverty in a sparsely-furnished apartment in New York City and wrote an article entitled “The Forgotten Man.” That prompted a fundraiser that ended up providing him with a small monthly stipend for the rest of his life.

Langford died in January 1956, just shy of his 70th birthday, in the nursing home where he had resided for a little under three years. On one occasion not long before he passed, he urged a visitor that “Don’t nobody need to feel sorry for old Sam. I had plenty of good times. I been all over the world. I fought maybe 600 fights and every one of them was a pleasure.”

When his caretaker asked what he most wished he could do or where he would most like to go, he replied: “Missus, I’ve been everywhere I wanted to go. I’ve seen everything I wanted to see and I guess I’ve eaten just about everything that there is to eat. Now I just want to sit here in my room and not cause you any trouble.”

***

Asked to summarize Langford’s greatness, the late boxing historian Bert Sugar referred to the time Doc Kearns, Dempsey’s manager, turned down a chance for his man to face him.

“The funny thing about Langford is that he’s half-blind, and he comes to Doc Kearns in the ‘20s – and remember, Sam Langford has been fighting since the aughts – and he wants to fight Dempsey,” Sugar recalled. “And Doc Kearns says, ‘Sam, we were looking for somebody easier.’ He was half-blind, he was a goddamned middleweight, and he was that good.”

Johnson, the man who refused to give Langford a shot at the heavyweight crown, summed his old foe up pithily.

“Sam Langford,” he said, “was the toughest little son of a bitch who ever lived.”